It’s the goldilocks principle applied to training – what is the right amount of training load for you? And how far should you progress to optimise your training adaptations and prevent injury? Despite all the efforts and advancements made in this field over recent times, we don’t have a simple answer to those questions. The human body is an amazing, complex organism and we can’t always predict with 100% accuracy how it will react to training loads and stresses. But let’s discuss some of the ways you CAN monitor your training progression and load.

The 10% rule

The classic 10% rule – one of the first models for monitoring training progression. It basically states you should never increase subsequent training session load by more than 10%. For example, if you run 5km in one training session you shouldn’t run more than 5.5km in the next training session. This is an OK rule generally, especially for beginners, but it quickly breaks down for high-level athletes. You can see if you continually increased your training load by 10% you could reach breaking point pretty quick. Thankfully, we have developed more advanced training progression and load monitoring models in recent times.

Acute:chronic load ratio

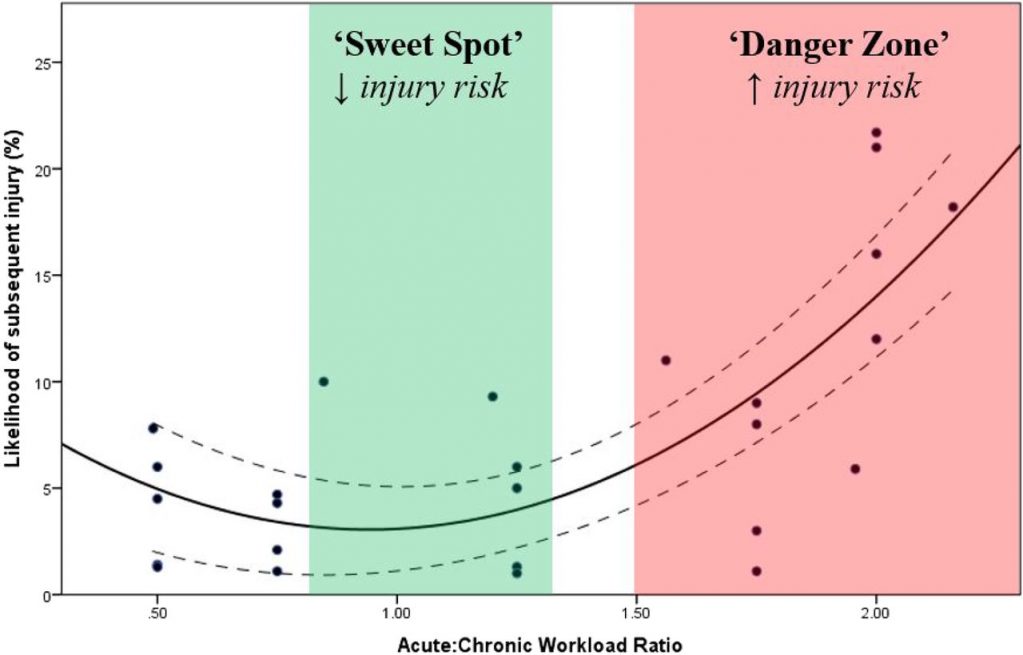

The acute:chronic load ratio was recently introduced by Gabbett et al. (2015). It models an athlete’s chronic workload (their average in the last month) with an athlete’s acute training load (the latest week of training). The model has been validated across three different sports — AFL, cricket and rugby league. It tells us that if your acute:chronic workload is between 0.8-1.3 you have a low chance of injury (less than10%). Conversely, the if the ratio is over 1.5 your likely injury risk more that doubles.

80/20 rule

The 80/20 rule applies more to training load than progression, and is mostly applicable to endurance sports. It states that for a given load of training 80% should be done at low to moderate intensity and 20% should be down at high intensities. I’m not aware of any high level research to support this, but it seems to work quite well anecdotally for elite and non-elite athletes.

General life, work and stress load

This is something a lot of people won’t necessarily take into account when quantifying their training progression and load. General life and work stress can take a massive toll on a person’s wellbeing and is probably a major divider between elite and sub-elite athletes. If you’ve worked a 50-hour work week trying to meet the end of month deadlines, it’s going to take a toll on your ability to recover and exert yourself. Commonly, I see age group athletes trying to balance all these commitments and end up sick, injured or over-stressed (and sometimes all three). However, there are some handy tools that can take this into account and help prevent you getting to the point of breaking down.

Monitoring your training (HRV, TSS, self-reporting)

With the advent of smart watches and cloud-based training management software there are now some great tools by which an athlete can self-monitor their training load.

HRV

Heart rate variability (HRV) is the difference in time between each individual heartbeat. For example, your heart rate may be 60 beats per minute, however there will be slight variation in the time between each beat. HRV increases over time with increasing fitness and it reduces with age. Most importantly for monitoring purposes, HRV reduces in response to training stress. Monitoring the effect of this stress on the body can help to determine the effectiveness of recovery strategies, the body’s readiness to train, identify and manage over training, and plan future training blocks. Read more about HRV here.

Training Stress Score (TSS)

Training Stress Score (TSS) is a number modelled from the duration and intensity of a training session to create an estimate of the overall training load and physiological stress created by that given training session. This is a really handy one as it’s automatically calculated in your training peaks or Garmin software and is quite easy to track over time. It’s mainly targeted at endurance athletes but some of the principles can be applied to all sports. For more info and to find out about the other metrics that are used in conjunction with TSS check out trainingpeaks.com

Self-reporting

Session-rating of perceived exertion (RPE) is a popular self-reported training method for athletes and coaches. At the end of each training session, athletes provide a 1–10 rating on the intensity of the session. The intensity of the session is multiplied by the session length (in minutes) to provide a measure of training load. Athletes and coaches will assess this load from week-to-week and month-to-month to help avoid both over and under training.

Questionnaires are also popular amongst athletes and coaches. There are many different types, ranging from simple Likert scale questionnaires to more detailed long-answer surveys. The surveys generally assess athlete’s mood, stress level, energy, sleep and diet, along with their feelings of soreness to determine the readiness to train and compete. Coaches and athletes use this data to adapt and change the training loads to avoid burnout and injury.

Coaching

As with the above training monitoring methods, having someone other than yourself keeping an eye on your training load and progression can be an invaluable tool. Coaches will lend and extra set of (hopefully unbiased) eyes to your program. They are invaluable to both unmotivated and over-motivated athletes to ensure the right amount of training load is reached. They are also someone in which an athlete can confide in and gain mental strength from.

As you can see there are a myriad of ways to monitor your training load and progression. Whichever method you use, make sure you stick to it and are constantly evaluating its effectiveness through your general wellbeing, and your training and competition performances. If you have questions with any of the above, always feel free to drop us a line!

References

Gabbett, T. J. (2016). The training-injury prevention paradox: should athletes be training smarter and harder?. Br J Sports Med, bjsports-2015.

www.trainingpeaks.com

About the Author:

Dr. Nicholas Tripodi is a Co-director and Osteopath at the Competitive Sports Clinic located in the Essendon District. Nicholas has particular interests in sports injuries, exercise rehabilitation and running and cycling analysis.